A Crash Course in the Galician Language

Galicia, located in Spain’s northwestern corner, is one of the country’s greatest regions. When I lived there from 2013 to 2015, I couldn’t get enough of the glorious, fresh food, the green, lush countryside, and the grand, granite architecture. But I could only take canned sardines with me back home, we’ve got enough humidity here in Texas, and sadly the oldest buildings in suburban Plano date back not to the 1070s but the 1970s.

But what has stuck with me the most has been galego, the Galician language that I quickly picked up on after being immersed in it from day one at the elementary school I worked at. Closely related to Spanish (and even closer to Portuguese), it’s kind of like a de-nasalized Portuguese, pronounced like Spanish, and with an Italian intonation. Its endearing, musical (some might say whiny) rhythm has infected my accent in Spanish, and I can rattle off more seafood and rain-related terms in Galician than I can in English.

So, what if you’re going to Galicia and are terrified that your Spanish will be of no use? Don’t worry—everyone in Galicia speaks Spanish as well as Galician. But learning a little of the language can only help you in making friends, understanding conversations, and (most importantly!) reading menus. I’ve put together this crash course in galego that I hope will help you keep your head above water, whether you’re just there for a visit or moving to the region for a longer stay.

The Galician language is a direct descendant of the Latin language that the Romans introduced to Spain’s northwest corner, just as today’s French developed from the Latin spoken in northern France and standard Italian grew out of the Tuscan dialects in central Italy. As the Roman Empire collapsed in the 400s CE and communications broke down, the everyday Latin in this isolated region naturally evolved into a separate language altogether.

Today known as Galician-Portuguese, the language was spoken during the Middle Ages from the northern Atlantic shores down to the Portuguese Algarve. As the ragtag Christian kingdoms of northern Spain advanced south into the territory of Muslim al-Andalus, they also brought their respective Romance dialects with them. A narrow strip of Galician-Portuguese thus spread down the western edge of the Iberian Peninsula.

Poets, singers, and troubadours alike chose this vernacular to compose their songs of courtly love in, so much so that Galician-Portuguese enjoyed a status as the prestige language for lyric poetry in royal courts across the peninsula. This rich cultural heritage, however, would ultimately lose ground to Castilian Spanish.

Portugal gained its independence from the Kingdom of León in the 1100s, permanently severing Galicia from her sister to the south. As Galicia migrated into the Castilian sphere of influence, Spanish quickly became the only language accepted in the courts, relegating non-Castilian tongues to conversations in the home and the countryside. It would take centuries for the dialects on either side of the Spanish-Portuguese border to part their ways, but by the modern era, Galician and Portuguese had emerged as two distinct languages.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that Galician regained its status as a literary language during the Rexurdimento or Galician Renaissance. Trailblazing authors like Rosalía de Castro began to publish poems written in Galician and challenged the notion that only Castilian was suitable in the business, legal, and literary worlds.

After a brutal civil war in the 1930s, Spain under dictator Franco became a uniform, nationalist country in which everyone went to Mass on Sunday and everyone spoke Spanish; all other languages were banned from public society. Once Franco died in 1975, though, Spain opened up and minority languages like Galician were finally allowed to be used in government, education, and the media. Today, Galician and Spanish are co-official in the region of Galicia.

As you might expect, Galician is spoken across the entire autonomous community of Galicia, but it also stretches further east into border areas like far-western Asturias and the Bierzo sub-region in northwest León.

Within Galicia proper, there’s a large urban-rural linguistic divide: the bigger the city, the smaller the percentage of Galician native speakers. Although the vast majority of people who live here are fluent in both Castilian Spanish and Galician, there are many people who either grew up speaking Spanish at home or simply feel more comfortable speaking Spanish in their daily lives—and it doesn’t help that in the two biggest cities, A Coruña and Vigo, you hardly hear Galician spoken on the streets.

The language is in no danger of dying out, what with official recognition, mass bilingual education, and freedom to speak it in public, but as the countryside continues to empty into the provincial capitals, I fear that Galician will be used less and less.

There are a bajillion exceptions to this rule that are way too complicated to explain in this crash course, but the biggest one to be aware of is negatives. So, you can say Fágoche un café? (“Shall I pour you a cup of coffee?”) but also Non me fagas un café (“Don’t pour me a cup”) where the object pronoun me comes before the verb instead of after.

Not so in Galician! While this sometimes means you can’t talk about the past (or what “would have had to have happened”) with such minute precision as you can in Spanish, it makes picking up on the language fairly easy. Where Spanish has a total of TEN simple and compound verb tenses in the indicative mood, Galician has a more manageable six: present, imperfect, past, a unique tense called the antepretérito for things like “I had said,” the future, and the conditional. Easy as pie!

If a word ends in the letters R or Z, you add -ES to the end as you would in Spanish. If you have more than one noz (“walnut”), then you’ve got some noces.

And if a word ends in the letter L, it will take the plural -ES form like normally unless the word’s stress falls on the last syllable. Then the L transforms into -IS. Fun!

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

More examples:

You pronounce Galician almost exactly the same as you would modern Castilian Spanish, except for three major differences:

Why these three verbs, and why only the past and present forms? Well, in my experience being bombarded with galego every day at the school I worked at, these were the three most commonly-used irregular verbs; i.e., they have verb forms that don’t follow the regular rules most other verbs follow so it’s harder to pick up on them unless you know what to listen for. And the past tense for these three verbs is radically different, so it’s helpful to keep them in mind during conversations.

Have you tried studying Galician before? Or have you picked up one of the other minority languages in Spain, like Catalan or Basque? Share your language-learning experiences below in the discussion thread! And don’t hesitate to ask any questions you have about Galician in the comments!

But what has stuck with me the most has been galego, the Galician language that I quickly picked up on after being immersed in it from day one at the elementary school I worked at. Closely related to Spanish (and even closer to Portuguese), it’s kind of like a de-nasalized Portuguese, pronounced like Spanish, and with an Italian intonation. Its endearing, musical (some might say whiny) rhythm has infected my accent in Spanish, and I can rattle off more seafood and rain-related terms in Galician than I can in English.

So, what if you’re going to Galicia and are terrified that your Spanish will be of no use? Don’t worry—everyone in Galicia speaks Spanish as well as Galician. But learning a little of the language can only help you in making friends, understanding conversations, and (most importantly!) reading menus. I’ve put together this crash course in galego that I hope will help you keep your head above water, whether you’re just there for a visit or moving to the region for a longer stay.

Quick overview of this post

- A bit of a background

- Where Galician is spoken today

- Six Galician grammar points if you already know Spanish

- Ten tricks to figuring out what a Galician word means if you already know Spanish

- How to pronounce Galician

- Some basic vocabulary

- Some useful expressions

- Three important irregular verbs, conjugated

- Online resources

1) A bit of a background

|

| A bandeira galega—the Galician flag |

The Galician language is a direct descendant of the Latin language that the Romans introduced to Spain’s northwest corner, just as today’s French developed from the Latin spoken in northern France and standard Italian grew out of the Tuscan dialects in central Italy. As the Roman Empire collapsed in the 400s CE and communications broke down, the everyday Latin in this isolated region naturally evolved into a separate language altogether.

Today known as Galician-Portuguese, the language was spoken during the Middle Ages from the northern Atlantic shores down to the Portuguese Algarve. As the ragtag Christian kingdoms of northern Spain advanced south into the territory of Muslim al-Andalus, they also brought their respective Romance dialects with them. A narrow strip of Galician-Portuguese thus spread down the western edge of the Iberian Peninsula.

Poets, singers, and troubadours alike chose this vernacular to compose their songs of courtly love in, so much so that Galician-Portuguese enjoyed a status as the prestige language for lyric poetry in royal courts across the peninsula. This rich cultural heritage, however, would ultimately lose ground to Castilian Spanish.

Portugal gained its independence from the Kingdom of León in the 1100s, permanently severing Galicia from her sister to the south. As Galicia migrated into the Castilian sphere of influence, Spanish quickly became the only language accepted in the courts, relegating non-Castilian tongues to conversations in the home and the countryside. It would take centuries for the dialects on either side of the Spanish-Portuguese border to part their ways, but by the modern era, Galician and Portuguese had emerged as two distinct languages.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that Galician regained its status as a literary language during the Rexurdimento or Galician Renaissance. Trailblazing authors like Rosalía de Castro began to publish poems written in Galician and challenged the notion that only Castilian was suitable in the business, legal, and literary worlds.

After a brutal civil war in the 1930s, Spain under dictator Franco became a uniform, nationalist country in which everyone went to Mass on Sunday and everyone spoke Spanish; all other languages were banned from public society. Once Franco died in 1975, though, Spain opened up and minority languages like Galician were finally allowed to be used in government, education, and the media. Today, Galician and Spanish are co-official in the region of Galicia.

2) Where Galician is spoken today

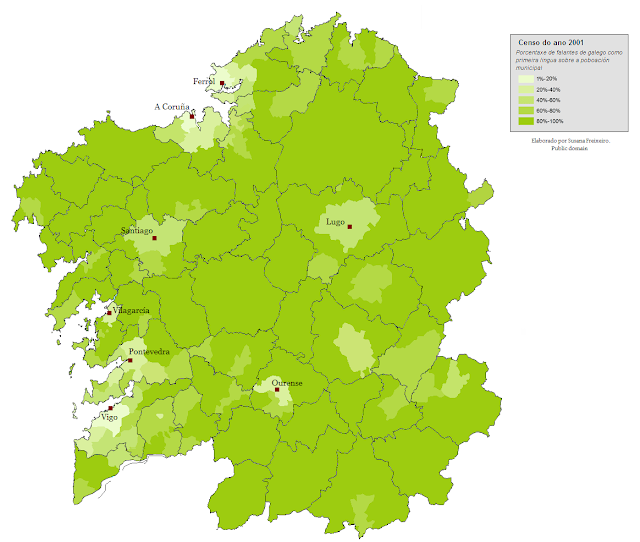

|

| Percentage of native Galician speakers by municipality |

As you might expect, Galician is spoken across the entire autonomous community of Galicia, but it also stretches further east into border areas like far-western Asturias and the Bierzo sub-region in northwest León.

Within Galicia proper, there’s a large urban-rural linguistic divide: the bigger the city, the smaller the percentage of Galician native speakers. Although the vast majority of people who live here are fluent in both Castilian Spanish and Galician, there are many people who either grew up speaking Spanish at home or simply feel more comfortable speaking Spanish in their daily lives—and it doesn’t help that in the two biggest cities, A Coruña and Vigo, you hardly hear Galician spoken on the streets.

The language is in no danger of dying out, what with official recognition, mass bilingual education, and freedom to speak it in public, but as the countryside continues to empty into the provincial capitals, I fear that Galician will be used less and less.

3) Six Galician grammar points if you already know Spanish

1) Articles

The Galician “the” is simply a single vowel: o in front of masculine words and a before feminine ones. Where Spanish has el, la, los, and las, Galician has o, a, os, and as. Because Galician and Portuguese lost that initial L over the centuries, their articles make for some fun, and sometimes confusing, contractions.2) Contractions

Galician’s got a lot, mainly having to do with prepositions. I’ve used articles in the examples below, but pronouns can combine, too.- a (“to”) and an article: ao, á, aos, ás

- con (“with”) and an article: co, coa, cos, coas

- de (“of”) and an article: do, da, dos, das

- en (“in, on”) and an article: no, na, nos, nas

- por (“by, for”) and an article: polo, pola, polos, polas

3) Possessive pronouns

They differ from Spanish in two significant ways: they almost always carry a definite article (o, a, os, or as) in front and they change form depending on the grammatical gender of the noun they belong to. “My mother” in Galician—a miña nai—literally translates to “the my mother.”- O meu/a miña = my

- O teu/a túa = your

- O seu/a súa = his/hers/its

- O noso/a nosa = our

- O voso/a vosa = y’all’s

- O seu/a súa = their

4) Object pronouns follow verbs…most of the time

In Spanish, object pronouns (think “him,” “me,” “them,” etc.) usually squeeze in between the subject and the verb; e.g., Él me dijo lo que pasó (“He told me what happened.”). In Galician, though, the object pronouns attach themselves to the ends of the verbs: El díxome o que pasou, which is actually closer to how we form sentences in English when you think about it.There are a bajillion exceptions to this rule that are way too complicated to explain in this crash course, but the biggest one to be aware of is negatives. So, you can say Fágoche un café? (“Shall I pour you a cup of coffee?”) but also Non me fagas un café (“Don’t pour me a cup”) where the object pronoun me comes before the verb instead of after.

5) There are no compound verb tenses

Spanish grammar holds an infamous reputation among upper-level college students for all the dizzying subtleties between the simple future, the future perfect, the pluperfect, etc. being so incredibly difficult to figure out. Most of our headaches come from compound verb tenses, which are made by combining a helping verb like haber with the past participle of a regular ol’ verb like comer or beber.Not so in Galician! While this sometimes means you can’t talk about the past (or what “would have had to have happened”) with such minute precision as you can in Spanish, it makes picking up on the language fairly easy. Where Spanish has a total of TEN simple and compound verb tenses in the indicative mood, Galician has a more manageable six: present, imperfect, past, a unique tense called the antepretérito for things like “I had said,” the future, and the conditional. Easy as pie!

6) Forming plurals is simpler—and more confusing

If a word ends in a vowel or the letter N, you just add an S to the end and call it a day. “A dog” in Galician is un can, so “some dogs” would be uns cans.If a word ends in the letters R or Z, you add -ES to the end as you would in Spanish. If you have more than one noz (“walnut”), then you’ve got some noces.

And if a word ends in the letter L, it will take the plural -ES form like normally unless the word’s stress falls on the last syllable. Then the L transforms into -IS. Fun!

- one fósil, two fósiles

- one bol, two boles

- one animal, two animais

4) Ten tricks to figuring out what a Galician word means if you already know Spanish

1) E instead of IE

The Spanish diphthong IE finds its way into many beautiful words like cielo (“heaven”) and tierra (“earth”), but those words’ Galician counterparts have only a short E vowel instead: ceo and terra. Make sure to pronounce these words with the “eh” sound as in the English words “bet” and “peck.”More examples:

- Spanish hierro, Galician ferro (“iron”)

- Spanish pienso, Galician penso (“I think”)

- Spanish quiero, Galician quero (“I want”)

2) O instead of UE

The UE diphthong is also everywhere in Spanish, but fuego (“fire”) in Galician is actually fogo, with a short O vowel instead. Make sure to pronounce such words with the “oh” sound as in the English words “for” and “lord.”More examples:

- Spanish juego, Galician xogo (“game”)

- Spanish nuestro, Galician noso (“our”)

- Spanish puede, Galician pode (“he/she can”)

3) EI instead of E

One of Galician’s most endearing traits, drawn-out diphthongs make the word for cheese—queixo—a lot more fun to say than Spanish’s queso. These Southern drawl-style vowels are part of what makes Galician have such a musical lilt.More examples:

- Spanish extranjero, Galician estranxeiro (“foreigner”)

- Spanish madera, Galician madeira (“wood”)

- Spanish primero, Galician primeiro (“first”)

4) OU instead of O

Where Spanish has a simple O sound, Galician has a stretched-out OU much like the way we pronounce the word “low” in English. While in Spanish you say él ganó for “he won,” in Galician it’s the longer el gañou.More examples:

- Spanish poco, Galician pouco (“few”)

- Spanish oro, Galician ouro (“gold”)

- Spanish otro, Galician outro (“other”)

5) Rs instead of Ls

Whenever Ls followed Latin Bs and Ps, they often switched to Rs as they grew up into Galician words. Restaurants in the rest of Spain will advertise their plato del día or daily special on their windows, but in Galicia you should look for a prato do día.More examples:

- Spanish blanco, Galician branco (“white”)

- Spanish playa, Galician praia (“beach”)

- Spanish plaza, Galician praza (“town square”)

6) Nothing instead of Ls and Ns in the middle of words

The Galician name for the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires, is simply Bos Aires—hey now, where’d half those letters go? When the Latin spoken in Roman Galicia transformed into Galician-Portuguese, any Ns that happened to hang out between two vowels were simply kicked out and never seen again. Thus, Spanish bueno and buena are just bo and boa in Galician.More examples:

- Spanish luna, Galician lúa (“moon”)

- Spanish persona, Galician persoa (“person”)

- Spanish salida, Galician saída (“exit”)

7) Ls and Ns instead of LLs and Ñs in the middle of words

Where Spanish has a “ly” and “ny” sound in words like ellos (“them”) and otoño (“autumn”), Galician has simply eles and outono with plain Ls and Ns.More examples:

- Spanish año, Galician ano (“year”)

- Spanish bello, Galician belo (“beautiful”)

- Spanish castillo, Galician castelo (“castle”)

8) Ñs instead of Ns in the middle of words

Almost the reverse of #7 above, in some places where Spanish has an N between two vowels, Galician often throws a tilde on it, just for kicks, so the Spanish word for “flour,” harina, is fariña in Galician.More examples:

- Spanish reina, Galician raíña (“queen”)

- Spanish sardina, Galician sardiña (“sardine”)

- Spanish vino, Galician viño (“wine”)

9) X/LL instead of J/G

For me, the most exciting difference between Spanish and Galician is that all those harsh, guttural Js and Gs in Castilian get replaced by smooth, gliding double LLs and soft, slushy SH sounds in the form of the letter X. While you might pronounce the Spanish word for “ham”—jamón—with a loud, throaty KH sound, in Galician, though, xamón sounds like “shah-MOWNG.” There’s no hard and fast rule to figure out when a J goes with an X or when a G goes with an LL, so just have fun with it!More examples:

- Spanish mujer, Galician muller (“woman”)

- Spanish origen, Galician orixe (“origin”)

- Spanish reloj, Galician reloxo (“clock”)

10) Fs instead of Hs at the beginning of words

You pronounce the Spanish word for “leaf,” hoja, as “OH-khah,” but that hides the fact that it derives from an older Latin word that used to start with the letter F, related to the English word “foliage.” Galician kept that initial F over the ages, hence their word for “leaf” is folla.More examples:

- Spanish hacer, Galician facer (“to make/do”)

- Spanish herver, Galician ferver (“to boil”)

- Spanish higo, Galician figo (“fig”)

5) How to pronounce Galician

You pronounce Galician almost exactly the same as you would modern Castilian Spanish, except for three major differences:

- Like I said in the section above in points #1 and #2, Galician distinguishes between open and closed vowels for E and O—although this unfortunately isn’t reflected in the spelling, so it’s something you just have to practice. Remember, this is the difference between “late” and “let” and between “low” and “lore.”

- Galician also uses the NG sound in several words, spelled NH between vowels and, sneakily, just N at the ends of words. For the phrase “one thing”—unha cousa—you would say “OONG-ah KOH-OO-sah,” and the word for “dog”—can—sounds more like “Kong” than “tin can.”

- Finally, in place of Spanish’s throaty G and J, the letter X in Galician is equivalent to the SH in English.

Vowels

- a = “ah” as in “father”

- e (closed) = “ay” as in “pay”

- e (open) = “eh” as in “set”

- i = “ee” as in “bee”

- o (closed) = “oh” as in “lode”

- o (open) = “oh” as in “lord”

- u = “oo” as in “food”

Consonants

- b/v = at the beginnings of words, “b” as in “berry”; in between vowels, more like “v” as in “very”

- c/z = “th” as in “thin”

- ch = “ch” as in “church”

- d = “d” as in “dark”

- f = “f” as in “farm”

- g/gu = “g” as in “gum”

- c/qu = “k” as in “lake”

- l = “l” as in “love”

- ll = “y” as in “you”

- m = “m” as in “mom”

- n = “n” as in “nose”

- ñ = “ny” as in “canyon”

- nh/-n = “ng” as in “long”

- p = “p” as in “cap”

- r = American “tt” as in “butter”; one R at beginnings of words or an RR anywhere, a trilled R

- s = “s” as in “soy”

- t = “t” as in “cat”

- x = in most words, “sh” as in “short”; rarely, “ks” as in “box”

6) Some basic vocabulary

Pronouns

- Eu = I

- Ti = You

- El = He

- Ela = She

- Nós = We

- Vós = Y’all

- Eles/elas = They

Colors

- Negro = Black

- Gris = Gray

- Branco = White

- Rosa = Pink

- Vermello = Red

- Laranxa = Orange

- Amarelo = Yellow

- Verde = Green

- Azul = Blue

- Violeta = Purple

- Marrón = Brown

Numbers

- Un/unha = 1

- Dous/dúas = 2

- Tres = 3

- Catro = 4

- Cinco = 5

- Seis = 6

- Sete = 7

- Oito = 8

- Nove = 9

- Dez = 10

- Once = 11

- Doce = 12

- Trece = 13

- Catorce = 14

- Quince = 15

- Dezaseis = 16

- Dezasete = 17

- Dezaoito = 18

- Dezanove = 19

- Vinte = 20

- Vinte e un/unha = 21

- Vinte e dous/dúas = 22

- Vintetrés = 23

- Trinta = 30

- Corenta = 40

- Cincuenta = 50

- Sesenta = 60

- Setenta = 70

- Oitenta = 80

- Noventa = 90

- Cen = 100

- Cento un = 101

- Mil = 1,000

Days of the week

- Luns = Monday

- Martes = Tuesday

- Mércores = Wednesday

- Xoves = Thursday

- Venres = Friday

- Sábado = Satuday

- Domingo = Sunday

Months of the year

- Xaneiro = January

- Febreiro = February

- Marzo = March

- Abril = April

- Maio = May

- Xuño = June

- Xullo = July

- Agosto = August

- Setembro = September

- Outubro = October

- Novembro = November

- Decembro = December

Time

- Agora = Right now

- Antes = Before

- Despois = After

- Xa = Already

- Hoxe = Today

- Onte = Yesterday

- Mañá = Tomorrow

Directions

- Esquerda = Left

- Dereita = Right

- Todo recto = Straight ahead

- Norte = North

- Sur = South

- Leste = East

- Oeste = West

- Arriba = Up

- Abaixo = Down

7) Some useful expressions

Greetings

- Ola = Hi

- Bos días = Good morning

- Boas tardes = Good afternoon

- Boas noites = Goodnight

- Ata logo/ata loguiño = See you later

- Ata mañá = See you tomorrow

- Chau = Bye

- Adeus = Goodbye

Phrases

- Como estás? = How are you?

- Moi ben, e ti? = Fine, and you?

- Como te chamas? = What’s your name?

- Chámome… = My name is…

- Por favor = Please

- Grazas/graciñas = Thank you

- De nada = You’re welcome

- Síntoo = I’m sorry

- Desculpa = Excuse me (trying to get attention)

- Perdoa = Excuse me (asking for forgiveness)

- Permiso = Excuse me (squeezing through a crowd)

- Falas inglés? = Do you speak English?

- Non te entendo = I don’t understand you

- Eu non falo galego = I don’t speak Galician

- Fálasme en castelán, por favor? = Can you use Spanish, please?

- Que hora é? = What time is it?

- Tes a hora? = Do you have the time?

- Son as dez = It’s 10-o’-clock

- Si = Yes

- Non = No

- E = And

- Ou = Or

- Vale = OK

- Pois… = Well…/alright

At the bar/café/restaurant

- Posme un café, por favor = Can I have a cup of coffee, please?

- Quería… = I’d like…

- Está riquiño = It’s really good

- A conta, por favor = The check, please

- Cóbrasme? = What do I owe you?

- Onde están os servizos? = Where’s the toilet?

- Homes = Men

- Mulleres = Women

- Está aberto = It’s open

- Está pechado = It’s closed

8) Three important irregular verbs, conjugated

Why these three verbs, and why only the past and present forms? Well, in my experience being bombarded with galego every day at the school I worked at, these were the three most commonly-used irregular verbs; i.e., they have verb forms that don’t follow the regular rules most other verbs follow so it’s harder to pick up on them unless you know what to listen for. And the past tense for these three verbs is radically different, so it’s helpful to keep them in mind during conversations.

Ser (to be)

Present

- Son = I am

- Es = You are

- É = He/she/it is

- Somos = We are

- Sodes = Y’all are

- Son = They are

Past

- Fun = I was

- Fuches = You were

- Foi = He/she/it was

- Fomos = We were

- Fostes = Y’all were

- Foron = They were

Dicir (to say)

Present

- Digo = I say

- Dis = You say

- Di = He/she/it says

- Dicimos = We say

- Dicides = Y’all say

- Din = They say

Past

- Dixen = I said

- Dixeches = You said

- Dixo = He/she/it said

- Dixemos = We said

- Dixestes = Y’all said

- Dixeron = They said

Facer (to make/do)

Present

- Fago = I make/do

- Fas = You make/do

- Fai = He/she/it makes/does

- Facemos = We make/do

- Facedes = Y’all make/do

- Fan = They make/do

Past

- Fixen = I made/did

- Fixeches = You made/did

- Fixo = He/she/it made/did

- Fixemos = We made/did

- Fixestes = Y’all made/did

- Fixeron = They made/did

9) Online resources

- Cursodegallego.com: covers everything in the language, lots of activities & audio

- Dicionario de pronuncia da lingua galega: pronunciation guide that uses IPA symbols

- O galego para… aprendelo - O Portal da Lingua Galega: home page from the regional government with free downloads for entire textbooks & audio files; click on Celga 1–5 depending on your level

- Galician (Galego) - Omniglot: great overview of the language with recordings

- Galician language - Wikipedia: exhaustive introduction to the language

- Galician phrasebook - Wikitravel: practical Galician phrases & vocab for English-speakers

- Help:IPA for Galician - Wikipedia: phonetic guide to pronouncing Galician

- La Voz de Galicia: Galician-language edition of Galicia’s major newspaper

- Open Guide to Galician Language: super informative background to Galician (in English!)

- Tradutor Automático Gaio - Xunta: an English-Spanish-Galician online translator from the regional government

Have you tried studying Galician before? Or have you picked up one of the other minority languages in Spain, like Catalan or Basque? Share your language-learning experiences below in the discussion thread! And don’t hesitate to ask any questions you have about Galician in the comments!