Hiking to The Wave in Vermilion Cliffs National Monument

|

| The Wave |

As I sized up a formidable switchback, my gut told me, “don’t even think about it!”

That morning, my hiking buddies and I had trekked across a field of sagebrush, junipers, and yuccas into a small valley, gradually making our way up a gentle canyon wall in search of natural arches as a warm-up before continuing onto The Wave, a dazzling orange-and-white-striped rock formation on the Arizona–Utah border made famous by a Windows 7 wallpaper. After successfully finding the stiletto-shaped High Heel Arch and cetacean Moby Dick Arch, we were inspired to continue hiking further up in search of Dicks Arch, discovered just one month before.

|

| Moby Dick Arch |

Brian and Steve had already made it up, and I was next in line. I felt stuck—how was I supposed to make it up this sandy rock face with hardly anything to grab a hold of? I alternated between freezing in place and attempting to find a foothold as that inner voice suggested I go no further. Silencing that voice, I plowed ahead and reached for a slab of sandstone above my body to stabilize myself. Yet as I tried to move on up the switchback, the rock came loose and started to slide towards me! I managed to avoid a worst-case scenario (like a direct hit to my lower back), but the sandstone nevertheless slammed onto my right hand as it lurched down the trail. Three of my fingers hurt intensely, while a deep cut ran down my middle finger from the nail to the topmost knuckle.

I instantly regretted not listening to my instincts and felt way in over my head for a wilderness injury like this. My anxiety kicked into high gear and I immediately started panicking about having to end this hike to a world-famous destination early as well as the implications for my keyboard-, mouse-, and camera-based line of work.

But thanks to know-how and care from my hiking partner Dan, who regularly spends weeks traversing (in my mind) absolutely miserable conditions in the Grand Canyon, my right hand was loaded up with enough gauze and tape to hold me over for 8 hours—just enough time to proceed with our hike to The Wave.

|

| Hiking through the wilderness |

I was shaken up, for sure, and felt embarrassed and unprepared with my city-slicker Herschel backpack, 2 liters of water, and minimalist running shoes, but I was game enough to keep going to see this rock formation others wait literal years to visit. My pinky finger could still reach my camera’s shutter button, and that’s what really counts, right?

After my run-in with the sandstone slab, a bighorn ram graced our path as it climbed over a ridgeline in the distance. It was the only sign of life on these layers of slickrock, so we took this as a good omen, slid down the sand hills, and returned to the main trail to The Wave.

What are the Vermilion Cliffs?

As you move north from the Grand Canyon into Utah, you’ll run into sedimentary layers of rock that have eroded away in a stair-step pattern of broad plateaus and steep cliffs called the Grand Staircase. The Vermilion Cliffs, the second of these five larger-than-life steps, tell a geologic tale of eons ago when Arizona and Utah were buried under the largest expanse of sand dunes planet Earth has ever seen. The Wave emerges from the candy-cane stripes of this 180-million-year-old Navajo Sandstone.

|

| The Vermilion Cliffs |

The cliffs encircle a plateau containing a wonderland of landscapes, including multicolor layers of sandstone, dinosaur tracks, “brain rocks,” boxwork, quicksand…you name it. The whole region—cliffs, plateau, and the canyon carved by the Paria River—was declared a national monument by President Clinton in 2000. The Bureau of Land Management, uh, manages recreation on this land, restricting access to the popular Coyote Buttes area (where The Wave is) to protect it for future generations.

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument also sees the yearly release of young California condors that were bred in captivity. This gigantic species of vulture almost went extinct in the 1980s, but its population has since rebounded to just over 500 birds. Many now like to hang out in this remote part of the continent.

Riding The Wave

Unlike condors, I don’t have much of an internal compass. I relied on my hiking partners Dan and Steve for directions as they had brought along detailed topographic maps. Brian had even downloaded a GPS-based map app onto his phone that would later help us find some dinosaur footprints. This congressionally designated wilderness is the kind of place where cairns are knocked over and developing trails swept away. Once I caught sight of a distinct vertical crevice in the rock, however, I knew exactly where we needed to go. I may not be able to navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field, but I felt inexplicably drawn up a slope toward The Wave.

|

| Entering The Wave |

As I entered an opening in the sandstone layers, it felt like I was entering a holy space: a nave of canyon walls rose up around me as I crept around a font of collected rainwater. The air was hushed, and I chose my steps carefully so as not to damage the sandstone. What forces of nature had built up, buried, and revealed over millions of years, humans consecrated with our pilgrimages on foot, our sacred midday meals of sandwiches and energy bars, and our ritual commemorative photo shoots.

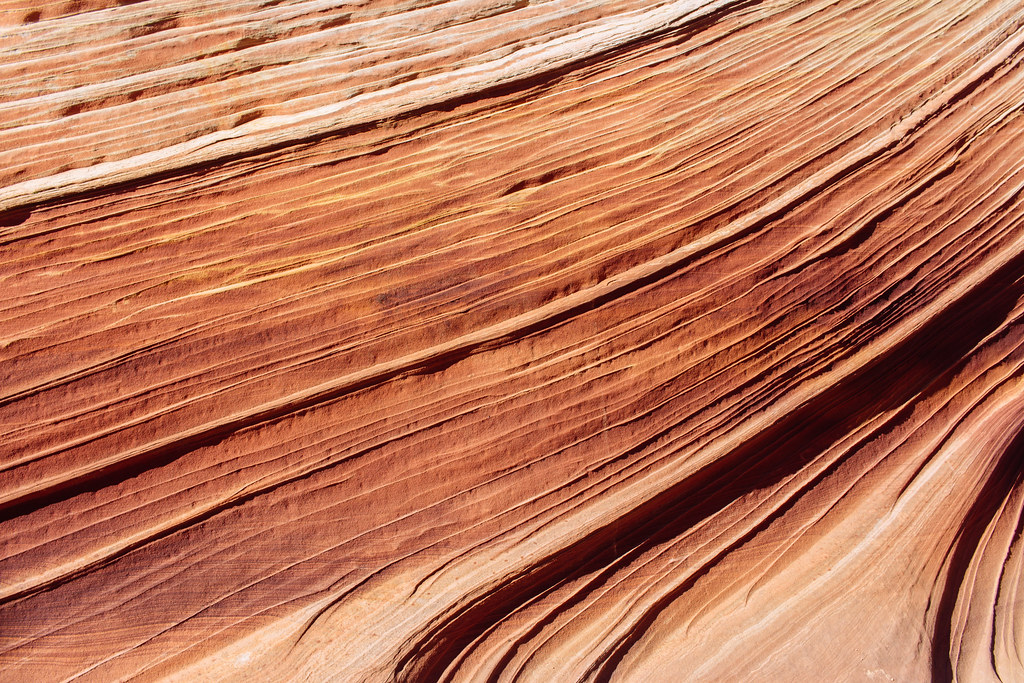

When the brief canyon opened up again, I found myself in a vast bowl of dizzying, dazzling stripes. I wondered if in my hand-injury delirium, I was hallucinating a confectioner’s hard candy mixing bowl—but this was really real. My spontaneous decision to hop along this trip the week before, plus my perseverance after enduring a slab of rock to my hand earlier that morning, had both paid off and allowed me to experience a wonder of the world that people wait years to visit.

|

| Stripey sandstone |

In between bites of a lukewarm Subway sandwich, I held my hand wrapped in gauze and bandages up above my heart, but I decided not to worry about my injuries and simply be present in the moment from my perch overlooking The Wave.

What struck me most was the deep, utter silence that dominated this landscape of pointy hills multiplying out to the horizon: no planes, no birds, no drones, no ATVs, not even the wind: just absolutely nothing but my own (elevated) heartbeat in my ears.

The specter of over-visitation

Only 20 people were allowed to visit the permit area that day in November 2016, and we ran into most of them. The Wave was busy at lunchtime, but you could still manage to get a photo for the ’Gram without anyone bombing your shot.

|

| Half the maximum number of visitors for the day in one photo—at the time |

One visitor at The Wave had a, uh, bowel emergency and asked around for some toilet paper…but he brought no shovel to dig a cathole or a plastic bag to pack out his used TP as he ascended to some slick rock further up. I’m sure he wasn’t the only unprepared hiker at The Wave that day—or in the past ten years.

Since then, the Bureau of Land Management has more than tripled the capacity at The Wave from 20 hikers per day to a maximum of 64 people.

|

| Clumps of cyanobacteria holding the soil together |

I’m concerned about keeping the delicate rock formations here safe, protecting the region’s fragile cryptobiotic soil, and keeping search-and-rescue missions at a minimum, but I recognize how frustrating it must be for the hundreds of thousands who have tried to visit The Wave for months, if not years, but can’t because the BLM has kept the number of permits so low. As someone who got to hike here only because someone originally in our group had to cancel at the last minute, it’s not fair for me to espouse a “screw you, I’ve got mine” attitude and gatekeep this wondrous location. Still, I hope that the BLM actively monitors conditions at The Wave and takes action to prevent it from turning into the next Horseshoe Bend.

After The Wave

The Wave is spectacular. But it’s merely the most spectacular point of an already sublime landscape. Emerging from a layer of Navajo Sandstone, The Wave is surrounded by undulating rockscapes in a warm spectrum of whites, oranges, and yellows. These steep hills and ridges represent an astonishing record of millions of years of shifting sand dunes and weather patterns now revealed to us after the strata on top were simply washed away.

|

| Landscape right outside The Wave |

There were even three-toed dinosaur footprints on an expanse of sandstone a short walk from The Wave!

Once we were back in Page, Arizona, we stopped off at the local urgent care to get me all patched up. Sitting in the waiting room, I felt like a statistic, as just another unprepared adventure-seeking visitor to this unforgiving region. But I was grateful that my situation was minor, that my hiking partners knew what to do in a crisis—and that I had health insurance. A nurse ended up rolling me across the town’s main drag in a wheelchair for X-rays at the hospital, then back to the urgent care facility to get stitches on my middle finger. The diagnosis? A fractured distal phalanx, my first-ever broken bone. I would have to wear a splint on my middle finger for the next month and deal with sensitive tissue on my fingertip for the next year.

After a cool shower at the hotel and a change of clothes, we regrouped for Mexican food and a well deserved Corona. I had almost gotten pulled under by The Wave’s backwash, but nevertheless got to experience one of the wonders of Arizona.

How to get there

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument on the Arizona–Utah border protects The Wave rock formation. Start your hike at the Wire Pass Trailhead, which is 8.4 miles south of U.S. Highway 89 on House Rock Valley Road—roughly halfway between Kanab, Utah, and Page, Arizona. You’ll need a high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle to get there. The National Park Service updates conditions for area roads here; scroll down to the bottom and look for House Rock Valley Road. I’d reconsider any trip in this region after winter snow or summer monsoon rains. This is desert wilderness country, so plan to bring at least 3–4 liters of water, sunscreen, a wide-brimmed hat, and comfortable shoes for hiking across both sand and rugged terrain.

|

| Some of the Coyote Buttes |

It’s free to go hiking in the national monument, but the Bureau of Land Management restricts access to a slim wedge of land surrounding The Wave called Coyote Buttes North. You’re only allowed in if you win one of up to 64 daily permits in a lottery system split between entering online months in advance or the same day via a cellphone app while physically present in the region. Learn more about the lottery process here.

For more resources, check out TheWave.info and Hiking and Exploring the Paria River, a guidebook by Michael R. Kelsey.