San Millán de la Cogolla, the Cradle of the Spanish Language

|

| Fall landscapes in rural Rioja |

When traveling, some people seek out the best beaches or tranquil getaways, while others (the so-called “foodies”) research their destination’s tastiest dishes and the best places to eat them at. For me at least, I plan a lot of my trips around UNESCO World Heritage Sites, as I’m a big fan of historical sites and national parks. This program, associated with the UN since 1972, has recognized some of the planet’s most significant cultural and natural monuments. Spain has 44 such sites, making the country home to the third-highest concentration of Patrimonio de la Humanidad in the world.

|

| Vaulted cloisters in Yuso |

During my weekend trip out east to Logroño to visit my friend Mike in December, I got the chance to explore the Spanish region of La Rioja’s sole World Heritage Site: the Suso and Yuso Monasteries, out in the village of San Millán de la Cogolla. Although little known outside of this small province, these two monasteries are a great point of pride for riojanos. After all, Castilian Spanish was written down for the first time here in San Millán, and the first known poet in the Spanish language lived and worked here, too.

Mike told me that nearly all of the adult students he teaches at the language school insisted he visit the monasteries, so we took their advice and ventured out into the cold with a few other language assistant friends in Logroño.

Suso Monastery

San Millán’s story begins with, well, San Millán himself: St. Emilian of Cogolla, a monk who lived as hermit out here in the hills of Rioja in the 500s. After his death, his disciples started a small monastic community where the Suso Monastery is today, and this site slowly evolved over the centuries from its original Visigothic structure into the Mozarabic and Romanesque building we see today. I loved the eerie link to the past that the horseshoe-shaped arches gave as they cast shadows on the thousand-year-old floor and framed the coffins of a dozen or so monks. |

| Approaching the church |

In the 20th century, researchers working in the nearby Yuso Monastery (more on that below) discovered the Glosas Emilianenses while perusing the Codex Aemilianensis 60, one of many huge Latin tomes stored in the monastery’s library. These glosses—minor sidenotes written in the page margins—weren’t written in Latin but instead in the local vernacular language that had evolved from the Latin introduced by the Romans a thousand years prior.

The original codex or book was put together in the 9th or 10th centuries, but a hundred years later a scribe evidently felt the need to clarify certain words for future readers. Fortunately for us, he did so in Very Very Old Spanish, which gives us a fascinating peek into the Romance language dialects that would have been spoken in the area a millennium ago. When these glosses were discovered, they were considered to be the oldest written witness to the Spanish language.

|

| Inside the church |

Not long after an anonymous monk had scribbled down these notes in the page margins, another monk from the same monastery would go on to become the first known poet in the Spanish language. Gonzalo de Berceo lived from around 1196 to 1264 and was the monastery’s notary, a job that put him in contact with the community’s library and archives. It wasn’t long before he began writing hagiographies (religious biographies of saints) like the Life of St. Emilian and The Miracles of Our Lady. While the famous epic poem El Cantar del Mío Cid is older than Gonzalo’s works, we don’t know who wrote it, so Gonzalo de Berceo remains the oldest poet in Castilian Spanish.

It really is incredible that this tiny monastery in rural Rioja played such a formative role in the history of the Spanish language!

|

| Alabaster column capitals |

Yuso Monastery

|

| Outside the church |

So how’d there get to be two monasteries? Well, according to legend, in 1053 King García of Navarra tried to take St. Emilian’s body to a brand new monastery he had ordered to be built in nearby Nájera. However, just as the ox-drawn cart was getting into the river valley, the oxen abruptly stopped and refused to go any further. This was taken as a sign from heaven, a sign that Emilian didn’t want to be removed from the area, so the king decided to simply build another monastery and keep the saint’s relics in San Millán de la Cogolla.

The original hillside monastery came to be known as Monasterio de Suso, as suso is an archaic Spanish for “upper” or “above.” The new one received the name Monasterio de Yuso; yuso is a little-used word for “lower” or “below” (and, #NerdAlert, is cognate with the English word “dorsal”).

|

| The remains of St. Emilian |

The Yuso Monastery was later rebuilt in the 16th and 17th centuries making it a superb example of late Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles. The warm stone cloisters welcomed us in from the bitter cold weather outside, and the over-the-top golden Baroque decorations in the church dazzled us. The Spanish-language tour we went on took us throughout much of the monastery (which is still home to some Augustinian monks today!), the guide showed us some of their Most Ancient Books, and we got to gaze at the Romanesque carved ivory chest that holds the remains of St. Emilian.

It was kind of strange going on this tour because we were the youngest attendees by far; the group was composed almost entirely of retired Spaniards! But it was a pleasant change of pace to check out a destination that “only the locals” know about.

|

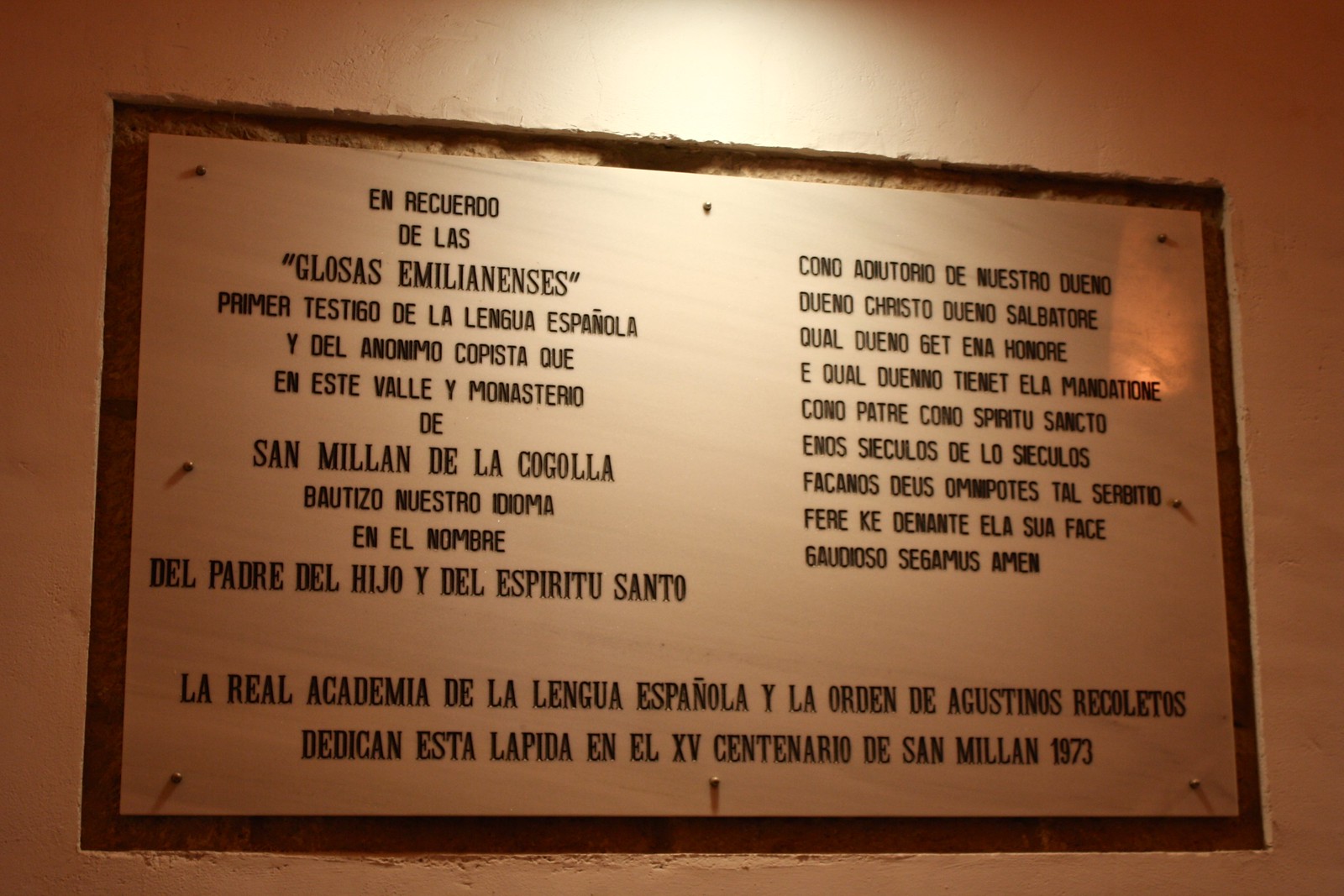

| Copy of the original text |

I left San Millán a little disappointed because the book that the Glosas Emilianenses were discovered in no longer belongs to the monastery; instead it’s in the library of Madrid’s Royal History Academy. There’s a huge plaque on the wall with the text of the sidenotes as well as a facsimile of the original page, but it’s just not the same thing as the real deal.

Also, recent studies have even cast doubt on Rioja’s status as the birthplace of Castilian Spanish. Many linguists believe that the language in the glosses is more accurately medieval Navarro-Aragonese, the predecessor to today’s endangered Aragonese language. It’s hard to say if a thousand years ago Navarro-Aragonese and old Castilian would have been mutually intelligible dialects of the same Romance language, though.

And to make matters worse, older manuscripts written in Old Castilian were found five years ago to the west in Burgos that date to the 800s, a whole century before the vernacular sidenotes were composed. None of these developments have been able, however, to dethrone San Millán de la Cogolla of its World Heritage status as the cradle of the Spanish language.

How to get there

|

| Beautiful Baroque sacristy |

These two monasteries belong to San Millán de la Cogolla, a village 40 minutes southwest of Logroño, the capital of La Rioja. Fortunately the company Autobuses Jiménez runs daily bus lines between Logroño and San Millán; check out the schedules here. I wouldn’t recommend making a daytrip here on the weekend as there is only one departure in either direction; i.e., you’re stuck in town for 12 hours. From Monday through Friday, though, you can take the 1pm bus from Logroño and then come back at 7:45pm.

Have you ever gone on a pilgrimage for a language before? Do the monasteries of Suso and Yuso sound interesting or boring to you? Tell me what you think below in the discussion thread!