Answering Your Questions About Walking Spain’s Camino de Santiago

Between June 5th and 9th of this year, I completed a major life goal by walking the Camino de Santiago, the ancient pilgrimage route that runs across northern Spain and ends at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela where the remains of St. James, son of Zebedee (a.k.a., Santiago), are reportedly buried.

Although ostensibly a religious route, the Camino is as much adventure and traveling as spiritual exercise. I only hiked 115km of it, but trekking 25km or more each day was a pleasant challenge and introduced me to the beautiful countryside of Galicia, the northwest region of Spain.

I’m sure most of you have a lot of questions about this pilgrimage, so in this post I’ve tried to answer most of the basic questions you may be asking. I’m sure to have missed some, so ask anything not in here in the comments below!

The legend goes that in the 1st century CE, the apostle James “the Greater” came to Roman Hispania (i.e., the Iberian peninsula) to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and establish the church there. He returned to Jerusalem, where he was martyred, but his body was miraculously translated to Galicia, washing up on a shore near Santiago. His grave was lost over the centuries.

In 831, however, a Galician shepherd named Pelayo saw what looked like stars falling over a forest. He went with the local bishop to the spot in the woods and there they found the sepulcher of St. James. The king ordered a chapel to be built over the remains and the rest, as they say, is history. Today James’ supposed remains are housed below the cathedral of Santiago, and a pope declared them to be real body of the saint, despite a serious lack of historical and even biblical evidence.

Putting things into historical context: James’ body was re-discovered barely a century after Muslims invaded the peninsula and dismantled the Catholic Visigothic kingdom. Christian noblemen had scattered to the mountains of the north, to places like Galicia, where they regrouped and began the Reconquista or “re-conquest” of Spain. This 700-year-long series of military campaigns would take on strong religious and nationalistic undertones, culminating in the expulsion of all non-Catholics in 1492.

St. James would frequently appear in battle and fight for the Christians (according to legend, of course) as Santiago Matamoros (“St. James the Moor-killer”), and ultimately became the patron saint of Spain. So the formation of what today we think of as Spain was intricately linked with this saint.

In the Middle Ages, the pilgrimage to St. James’ shrine in Santiago became the third-most popular route for western Christians after Jerusalem and Rome. After all, James himself had been part of Jesus’ inner circle (“Peter, James, and John” are frequently found together in the Gospels) and now he was leading the charge against the heathen Muslims in Spain! Ra-ra-ra!

People were particularly driven to make the hike during a Holy Year, or whenever James’ feast day (July 25th) fell on a Sunday. This is because the church would grant plenary indulgences—wiping out temporal punishment, that is, time spent in Purgatory—for anyone who came to town and confessed.

The Camino fizzled out in the early modern era, and only in the past two or three decades has it seen an immense jump in popularity. In the 1990s, barely 25,000 people walked it a year, but last year almost 200,000 pilgrims showed up in Santiago.

The Camino is a World Heritage Site and was the first European Cultural Itinerary, so it’s no cop-out to choose the “sólo cultural” option at all. The most popular route passes through four Autonomous Communities—Navarra, La Rioja, Castilla y León, and Galicia—as well as numerous cities of major historic significance, like Pamplona, Burgos, León, and, of course, Santiago de Compostela. You’ll encounter Basque-, Castilian-, and Galician-speaking Spaniards and enjoy a wide variety of local wines, cheeses, hams, and pastries. Architecture ranging from pre-Romanesque through Neoclassical will pop up in churches and palaces. If anything could be called Slow Travel, this is it.

But people will walk for whatever reason they want: adventure, the challenge, a vacation, meditation, meeting new people, exercise, tourism, restlessness, or just because it’s there.

I’m no Catholic, so I didn’t need time in Purgatory wiped out by the Church, but as a Christian living in the hyper-connected 21st century, I found the Camino a refreshing time of solitude and prayer away from a connection to the Internet or the demands of my phone, which I turned off for the duration of the hike. And as a big fan of Spain, I really enjoyed getting to know the region of Galicia for the first time, from its food to its architecture to, yes, even its rain.

But ever since finding out about the Camino, I had been transfixed by this idea of using my own two feet to walk across a beautiful country along an ancient way. It’s kind of hard to explain; I just had to walk it. They say the Camino “calls” you, or maybe it was just wanderlust. But I was really drawn to do this hike and am so glad I did. In the end, I declared religious and cultural reasons when I received the compostela (see below).

It really depends. First of all, in order to receive a certificate, the Pilgrims Office only requires you to prove on your pilgrim passport (see below) that you have walked the final 100km on foot or biked the last 200km.

Second, there are many paths to Santiago. By far the most popular route is the camino francés or the “French Way,” which begins in the French Pyrenees village of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, crosses into Spain via the mountains, and continues on for a total of 800km across northern Spain. Many choose to take the quieter, rougher camino del norte (“Northern Way”) instead, hugging the northern coasts of the Basque Country, Cantabria, and Asturias before dipping down into Galicia for the final stretch. The camino portugués (“Portuguese Way”) begins in Lisbon and heads due north, while the camino inglés starts in the coastal town of Ferrol and takes you south—the direction the English would have walked had they come by boat. Finally, the Vía de la Plata (“Paved Way”) links Sevilla via western Spain and the camino mozárabe (“Mozarabic Way”) draws pilgrims from across the southern part of the country.

Put simply, which route you take and where you begin it define how long your Camino will be. Mine was 115km, yours could be 1,000km!

(Going to blare the #nerdalert warning very loudly here!) A few years ago, I used to listen to my medieval/Renaissance choral music Pandora station to help me fall asleep, and this beautiful, ethereal album called The Road to Compostela by the Rose Ensemble kept popping up. I really liked the music, so I investigated it and quickly discovered that the choral group was singing medieval pieces from the Codex Calixtinus, basically the first pilgrim guidebook. I was fascinated by the idea of a month-long hike across northern Spain—a country I was just beginning to get interested in—and decided to put the pilgrimage on my bucket list.

Initially, I wanted to do the Camino right after graduating college in early May 2012, but foot problems and my failure to do any sort of training forced me to postpone purchasing air tickets indefinitely. However, once I found out I would be teaching in Spain for the next school year, I decided to plan on hiking the last five days of the Camino once summer break began. Why waste $1,000 on round-trip transatlantic plane tickets when you’re already in Spain?

Yes and no. Yes—I set off on this journey alone. No—within minutes of hopping off the bus in Sarria (the town where I started), I ran into a group of Americans and Brits who quickly became my walking partners for the whole Camino.

They were two retired couples from Connecticut—Dick & Wendy and Bob & Sandy. Bob and Dick were actually brothers and had hiked the Camino del Norte along the coast from Santander (I believe), where they met two natives of Oxfordshire, England—Rosie and Charlie. And Wendy and Sandy met up with them to do the last five days of the Camino in Sarria, like me.

I am so grateful I got to hike with these guys; they were really friendly and talkative, making the kilometers go by much faster than they would have otherwise. Plus, it was a lot of fun hearing their wild stories from the Camino del Norte, from fields of cow poop to crazy Russian hoteliers to a Frenchman who had walked the Camino 21 times.

Well, here’s what the typical Day in the Life of Trevor the Pilgrim looked like, assuming a 5km/hour average walking speed and 25km average daily hike:

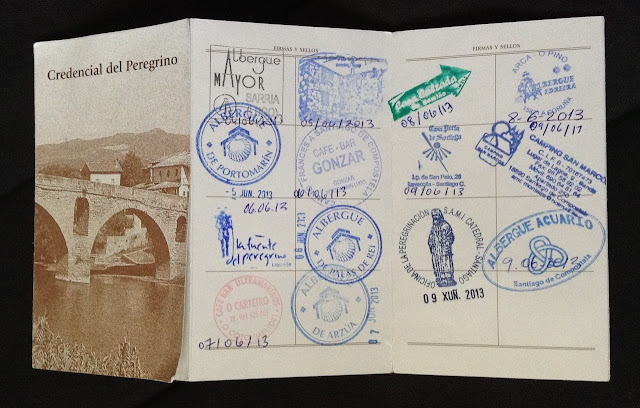

Think of the credencial as your passport along the Camino. At every albergue or pilgrim hostel you sleep in, you get it stamped to prove that, yes, you have walked EIGHT-HUNDRED kilometers (or 115km, if you’re like me) to the Church in Santiago. But it also serves an important quotidian function: it tells others (lit. gives credence to the fact) that you are a pilgrim, allowing you to stay in the super-cheap pilgrim hostels. You can also get your credencial stamped at bar/restaurant/cafés, churches, and other monuments along the way if you’re worried one stamp a day isn’t enough.

The private albergues were expectedly nicer, averaging 10€ a night, and they often had private showers, washers and dryers, and sometimes even WiFi. These were a real treat after a long, hard 30km slog of a day.

Both required you to present your pilgrim passport and some ID before checking in, and they usually only let you stay for one night. Sometimes there would be a spartan kitchen forburning making spaghetti in or some exterior sinks and clotheslines for washing your stinky hiking clothes. Lights-out was at 10pm (rarely 11pm), and you had to be out no later than 8 or 9am.

When I first got interested in hiking the Camino, I stumbled upon this blog written by a guy who walked the entire length of the pilgrimage in Vibram FiveFingers—minimalist “barefoot”-style gloves for your feet with Vibram rubber soles. I had always been uneasy about clomping around in massive hiking boots and worrying about washing wool socks, etc., so I was fascinated that it was humanly possible to do the Camino in FiveFingers. I loved the ones I already had (TrekSport), so I began practicing with them to build up the muscles in my feet and legs. Additionally, I exclusively wore flat-soled Vans and Converses to strengthen my feet.

For most of the hike, they were extremely comfortable and actually a lot of fun to wear, whether crawling over rocks or splashing through muddy streams. However, my feet tended to wear out past the 20km mark, and in Santiago, I was so sore that I was hobbling around the city in my flip flops. Also, the whole not-wearing-socks thing meant this repulsive stank developed inside the shoes, and although washing them in the shower helped, they were rarely dry by the morning. Still, I only got a single blister on my right foot.

I have no regrets about the footwear I chose—it was kind of fun getting lots of weird looks and giggles my way—but Trevor the Ten-Toed Texan would wear some kind of trainers or hiking shoes with socks the next time. I heard great things from my hiking friend Rosie about anti-blister 1,000 Mile Socks, so I’ll have to look into them. To be honest, I wouldn’t recommend VFFs for the Camino, but I nevertheless enjoyed the experience I had in them.

When you go to the Pilgrims Office in central Santiago to pick up your certificate that proves you hiked the Camino, you have to fill out your personal details on this form. One of the boxes you have to tick is motivación; i.e., why did you do it? Checking the boxes for religión and religión y otros will merit you a compostela, or a fancy, Latin-language certificate in red and black ink that states you piously came to Santiago to regard the tomb of St. James.

If you didn’t do the Camino for any spiritual reasons at all (otros), they will still give you a certificado, a simple document that welcomes you to the cathedral and is just as much proof of having walked it as the compostela is.

But there’s still 700 more kilometers of the pilgrimage I haven’t walked, and I would love to go back one day, start in St-Jean-Pied-de-Port in the French Pyrenees, and walk the camino francés through the beauty of Navarra and La Rioja, across the plains of Castilla, over the mountains of Bierzo, and into Galicia where Santiago lies. It would be a good five-week journey, that’s for sure, but it would be an immensely satisfying experience to go the whole way from “start” to finish.

Have you ever hiked part or all of the Camino de Santiago? What other questions do you have about walking this ancient pilgrimage route? Join the discussion in the comments below!

|

| Me having finished the Camino |

Although ostensibly a religious route, the Camino is as much adventure and traveling as spiritual exercise. I only hiked 115km of it, but trekking 25km or more each day was a pleasant challenge and introduced me to the beautiful countryside of Galicia, the northwest region of Spain.

I’m sure most of you have a lot of questions about this pilgrimage, so in this post I’ve tried to answer most of the basic questions you may be asking. I’m sure to have missed some, so ask anything not in here in the comments below!

So, what is this Camino?

|

| An hórreo or granary, a very common sight in Galicia |

The legend goes that in the 1st century CE, the apostle James “the Greater” came to Roman Hispania (i.e., the Iberian peninsula) to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and establish the church there. He returned to Jerusalem, where he was martyred, but his body was miraculously translated to Galicia, washing up on a shore near Santiago. His grave was lost over the centuries.

In 831, however, a Galician shepherd named Pelayo saw what looked like stars falling over a forest. He went with the local bishop to the spot in the woods and there they found the sepulcher of St. James. The king ordered a chapel to be built over the remains and the rest, as they say, is history. Today James’ supposed remains are housed below the cathedral of Santiago, and a pope declared them to be real body of the saint, despite a serious lack of historical and even biblical evidence.

Putting things into historical context: James’ body was re-discovered barely a century after Muslims invaded the peninsula and dismantled the Catholic Visigothic kingdom. Christian noblemen had scattered to the mountains of the north, to places like Galicia, where they regrouped and began the Reconquista or “re-conquest” of Spain. This 700-year-long series of military campaigns would take on strong religious and nationalistic undertones, culminating in the expulsion of all non-Catholics in 1492.

St. James would frequently appear in battle and fight for the Christians (according to legend, of course) as Santiago Matamoros (“St. James the Moor-killer”), and ultimately became the patron saint of Spain. So the formation of what today we think of as Spain was intricately linked with this saint.

|

| 800km from start to finish |

In the Middle Ages, the pilgrimage to St. James’ shrine in Santiago became the third-most popular route for western Christians after Jerusalem and Rome. After all, James himself had been part of Jesus’ inner circle (“Peter, James, and John” are frequently found together in the Gospels) and now he was leading the charge against the heathen Muslims in Spain! Ra-ra-ra!

People were particularly driven to make the hike during a Holy Year, or whenever James’ feast day (July 25th) fell on a Sunday. This is because the church would grant plenary indulgences—wiping out temporal punishment, that is, time spent in Purgatory—for anyone who came to town and confessed.

The Camino fizzled out in the early modern era, and only in the past two or three decades has it seen an immense jump in popularity. In the 1990s, barely 25,000 people walked it a year, but last year almost 200,000 pilgrims showed up in Santiago.

And why do people walk it?

According to the official register at the Pilgrims Office in Santiago, you can choose to walk for religious reasons, cultural reasons, or religious and cultural reasons. People (mainly Spanish Catholics) still walk the pilgrimage for officially religious reasons, but you don’t have to be a baptized Catholic in order to claim religion as a motivation.The Camino is a World Heritage Site and was the first European Cultural Itinerary, so it’s no cop-out to choose the “sólo cultural” option at all. The most popular route passes through four Autonomous Communities—Navarra, La Rioja, Castilla y León, and Galicia—as well as numerous cities of major historic significance, like Pamplona, Burgos, León, and, of course, Santiago de Compostela. You’ll encounter Basque-, Castilian-, and Galician-speaking Spaniards and enjoy a wide variety of local wines, cheeses, hams, and pastries. Architecture ranging from pre-Romanesque through Neoclassical will pop up in churches and palaces. If anything could be called Slow Travel, this is it.

But people will walk for whatever reason they want: adventure, the challenge, a vacation, meditation, meeting new people, exercise, tourism, restlessness, or just because it’s there.

Why did you do the Camino?

|

| Medieval bridge |

I’m no Catholic, so I didn’t need time in Purgatory wiped out by the Church, but as a Christian living in the hyper-connected 21st century, I found the Camino a refreshing time of solitude and prayer away from a connection to the Internet or the demands of my phone, which I turned off for the duration of the hike. And as a big fan of Spain, I really enjoyed getting to know the region of Galicia for the first time, from its food to its architecture to, yes, even its rain.

But ever since finding out about the Camino, I had been transfixed by this idea of using my own two feet to walk across a beautiful country along an ancient way. It’s kind of hard to explain; I just had to walk it. They say the Camino “calls” you, or maybe it was just wanderlust. But I was really drawn to do this hike and am so glad I did. In the end, I declared religious and cultural reasons when I received the compostela (see below).

How long of a walk is it?

|

| Snail along the way |

It really depends. First of all, in order to receive a certificate, the Pilgrims Office only requires you to prove on your pilgrim passport (see below) that you have walked the final 100km on foot or biked the last 200km.

Second, there are many paths to Santiago. By far the most popular route is the camino francés or the “French Way,” which begins in the French Pyrenees village of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, crosses into Spain via the mountains, and continues on for a total of 800km across northern Spain. Many choose to take the quieter, rougher camino del norte (“Northern Way”) instead, hugging the northern coasts of the Basque Country, Cantabria, and Asturias before dipping down into Galicia for the final stretch. The camino portugués (“Portuguese Way”) begins in Lisbon and heads due north, while the camino inglés starts in the coastal town of Ferrol and takes you south—the direction the English would have walked had they come by boat. Finally, the Vía de la Plata (“Paved Way”) links Sevilla via western Spain and the camino mozárabe (“Mozarabic Way”) draws pilgrims from across the southern part of the country.

Put simply, which route you take and where you begin it define how long your Camino will be. Mine was 115km, yours could be 1,000km!

How did you hear about it in the first place?

|

| Waymarker |

(Going to blare the #nerdalert warning very loudly here!) A few years ago, I used to listen to my medieval/Renaissance choral music Pandora station to help me fall asleep, and this beautiful, ethereal album called The Road to Compostela by the Rose Ensemble kept popping up. I really liked the music, so I investigated it and quickly discovered that the choral group was singing medieval pieces from the Codex Calixtinus, basically the first pilgrim guidebook. I was fascinated by the idea of a month-long hike across northern Spain—a country I was just beginning to get interested in—and decided to put the pilgrimage on my bucket list.

Initially, I wanted to do the Camino right after graduating college in early May 2012, but foot problems and my failure to do any sort of training forced me to postpone purchasing air tickets indefinitely. However, once I found out I would be teaching in Spain for the next school year, I decided to plan on hiking the last five days of the Camino once summer break began. Why waste $1,000 on round-trip transatlantic plane tickets when you’re already in Spain?

What did you pack?

In my 40-liter backpack, I managed to stuff…- lightweight sleeping bag

- toiletries + first aid

- one set of synthetic hiking shirt + shorts + undies (I wore the other outfit)

- “evening wear” of a v-neck shirt + chino shorts

- rainjacket

- Vibram TrekSport FiveFingers

- flip flops

- microfiber towel

- guidebook

- book to read

- journal + pen

- Canon DSLR + 50mm lens + charger

- two 1-liter Nalgenes

- sunglasses

- combination lock

- iPod + headphones + charger

- cellphone

- wallet

- passport

- pilgrim passport

Did you hike alone or with friends?

|

| The rowdy bunch |

Yes and no. Yes—I set off on this journey alone. No—within minutes of hopping off the bus in Sarria (the town where I started), I ran into a group of Americans and Brits who quickly became my walking partners for the whole Camino.

They were two retired couples from Connecticut—Dick & Wendy and Bob & Sandy. Bob and Dick were actually brothers and had hiked the Camino del Norte along the coast from Santander (I believe), where they met two natives of Oxfordshire, England—Rosie and Charlie. And Wendy and Sandy met up with them to do the last five days of the Camino in Sarria, like me.

I am so grateful I got to hike with these guys; they were really friendly and talkative, making the kilometers go by much faster than they would have otherwise. Plus, it was a lot of fun hearing their wild stories from the Camino del Norte, from fields of cow poop to crazy Russian hoteliers to a Frenchman who had walked the Camino 21 times.

How much did it cost?

Every day, I averaged 3€ for breakfasts (both first and second, ahem), 10€ for lunch, 8€ for dinner, and 6€ for a bed, or about 30€ a day. Sometimes I would spend more for a privately run pilgrim hostel, a nicer dinner, or something at the pharmacy, which made it a 35€- or 40€-day. But I managed to keep expenses down to 30€ per day of hiking, or about $40. This was a small price to pay for the experience the Camino offered, though!What was your daily routine like?

|

| Hiking…the daily grind |

Well, here’s what the typical Day in the Life of Trevor the Pilgrim looked like, assuming a 5km/hour average walking speed and 25km average daily hike:

- 6:30am = brush teeth, get dressed, pack up

- 7:00am = have breakfast at a nearby café of a pastry and café con leche (espresso + steamed milk)

- 7:30am = hit the road

- 10:00am = have second breakfast at a bar/restaurant/café or just a mid-morning bathroom break

- 1:00pm = finish walking, arrive in town, find an albergue to sleep in

- 1:30pm = take off shoes, roll out sleeping bag, unwind a bit

- 2:00pm = dinner of a menú del día (10€, two-course set meal for pilgrims) with Camino friends at a local restaurant

- 3:00pm = shower, wash clothes, nap, journal, chill out

- 5:00pm = explore the town, get a snack at a bar/restaurant/café, hang out with other pilgrims

- 7:00pm = supper of small tapas here and there

- 10:00pm = lights-out at the albergue, fall asleep

What’s with all the shells?

As Galicia is on the coast, you can find seafood and shellfish in all parts of the region. In the Middle Ages, whenever pilgrims finished the Camino, they would pick up a scallop shell off the beach (or from their dinner?) and carry it back with them as proof of having walked to the shrine of St. James. Today, many pilgrims begin the walk with a shell attached to their backpack, and virtually all of the waymarkers or guideposts feature a yellow shell on a blue background.Tell me about the pilgrim passport (credencial).

|

| The credencial |

Think of the credencial as your passport along the Camino. At every albergue or pilgrim hostel you sleep in, you get it stamped to prove that, yes, you have walked EIGHT-HUNDRED kilometers (or 115km, if you’re like me) to the Church in Santiago. But it also serves an important quotidian function: it tells others (lit. gives credence to the fact) that you are a pilgrim, allowing you to stay in the super-cheap pilgrim hostels. You can also get your credencial stamped at bar/restaurant/cafés, churches, and other monuments along the way if you’re worried one stamp a day isn’t enough.

What were pilgrim hostels (albergues) like?

The public albergues run by the Xunta de Galicia (regional government) were affordable (only 6€ a night) and had dependable amenities: they were clean and offered plenty of beds, anti-bedbug pillow- and mattress-covers, and warm, communal showers. You’d end up seeing the same people day after day in these hostels even if you didn’t necessarily pass them in the morning while walking.The private albergues were expectedly nicer, averaging 10€ a night, and they often had private showers, washers and dryers, and sometimes even WiFi. These were a real treat after a long, hard 30km slog of a day.

Both required you to present your pilgrim passport and some ID before checking in, and they usually only let you stay for one night. Sometimes there would be a spartan kitchen for

How did you wash your clothes?

I was most concerned about this annoying logistical problem before beginning the walk, but it wasn’t that big of a deal. While showering with my all-in-one shampoo and body wash gel (gotta love men’s toiletries…), I drizzled some soap onto my shorts or my shirt, worked it up to a lather, and rinsed the clothes off in the shower stream. Many albergues had dedicated sinks or basins to do your laundry in, but I found it most convenient to get the dirt out all at once in the shower. Then I would simply hang-dry my items on a clothesline provided by the pilgrim hostel.What kind of shoes did you wear?

When I first got interested in hiking the Camino, I stumbled upon this blog written by a guy who walked the entire length of the pilgrimage in Vibram FiveFingers—minimalist “barefoot”-style gloves for your feet with Vibram rubber soles. I had always been uneasy about clomping around in massive hiking boots and worrying about washing wool socks, etc., so I was fascinated that it was humanly possible to do the Camino in FiveFingers. I loved the ones I already had (TrekSport), so I began practicing with them to build up the muscles in my feet and legs. Additionally, I exclusively wore flat-soled Vans and Converses to strengthen my feet.

For most of the hike, they were extremely comfortable and actually a lot of fun to wear, whether crawling over rocks or splashing through muddy streams. However, my feet tended to wear out past the 20km mark, and in Santiago, I was so sore that I was hobbling around the city in my flip flops. Also, the whole not-wearing-socks thing meant this repulsive stank developed inside the shoes, and although washing them in the shower helped, they were rarely dry by the morning. Still, I only got a single blister on my right foot.

I have no regrets about the footwear I chose—it was kind of fun getting lots of weird looks and giggles my way—but Trevor the Ten-Toed Texan would wear some kind of trainers or hiking shoes with socks the next time. I heard great things from my hiking friend Rosie about anti-blister 1,000 Mile Socks, so I’ll have to look into them. To be honest, I wouldn’t recommend VFFs for the Camino, but I nevertheless enjoyed the experience I had in them.

Tell me about the certificate (compostela).

When you go to the Pilgrims Office in central Santiago to pick up your certificate that proves you hiked the Camino, you have to fill out your personal details on this form. One of the boxes you have to tick is motivación; i.e., why did you do it? Checking the boxes for religión and religión y otros will merit you a compostela, or a fancy, Latin-language certificate in red and black ink that states you piously came to Santiago to regard the tomb of St. James.

If you didn’t do the Camino for any spiritual reasons at all (otros), they will still give you a certificado, a simple document that welcomes you to the cathedral and is just as much proof of having walked it as the compostela is.

Would you do it again?

Even though I only walked 115km, it was just enough to get the compostela to say “I did it.” So it’s officially off the bucket list, and I could die happy without regretting not having walked the Camino when I had the chance.But there’s still 700 more kilometers of the pilgrimage I haven’t walked, and I would love to go back one day, start in St-Jean-Pied-de-Port in the French Pyrenees, and walk the camino francés through the beauty of Navarra and La Rioja, across the plains of Castilla, over the mountains of Bierzo, and into Galicia where Santiago lies. It would be a good five-week journey, that’s for sure, but it would be an immensely satisfying experience to go the whole way from “start” to finish.

Have you ever hiked part or all of the Camino de Santiago? What other questions do you have about walking this ancient pilgrimage route? Join the discussion in the comments below!